Looking for new work from Stephen Trimble? I’m publishing my essays and posts at Medium.com now. For new work, go to my Medium home page. And let me know what you think! Thanks.

The Bright Edge

"…that lightness, that dry aromatic odor…one could breathe that only on the bright edges of the world." Willa Cather

The Mike File

Where have I been? Blogs are supposed to be lively and current, and The Bright Edge has been quiescent for a long while. Here’s why.

I’m working on a memoir. I’ve never told the story of my half-brother, Mike. After my parents died, long after Mike died, I’m finally ready. I’m well on my way to a first draft, and it’s been a fascinating journey. Here is the intro, to give you a hint of the book to come.

- Isabelle & Mike, 1943

Angry shouts fly through the open kitchen window like sprays of buckshot. I can’t unravel the words, because I cup my hands tight over my ears to block the sound.

A swirling column of dust specks gives me a focus for displacing my fear, a desperate distraction. I track the journey as each dust mote floats from deep shadows into blazing sunshafts.

I remember a blanket of summer heat; I still can smell the oil-stains on the concrete floor of the wood-framed garage attached to our little suburban house. I remember tucking and folding myself into a ball, squatting in my t-shirt and shorts, jamming my hipbones against the wall, trying to disappear.

I was six. My teenaged brother, my mother’s son from her brief and disastrous first marriage, was screaming at my mother in the kitchen. Mike towered over Isabelle, arms braced around her, caging her against the wall. His anger poured out, resentment at my father—his stepfather. Frustration, rage. My mother did her best to speak calmly, to talk him down.

Terrified, I ran out to the garage to hide.

I can reclaim few memories of life with my brother, Mike, beyond that summer day in 1957. Though I shared a bedroom with him for six years, I’ve blocked nearly every memory, even the good ones. The great tragedy of my mother’s life, Mike has long been gone. My mother and father, Isabelle and Don, are gone. No one survives to answer questions. And my mother and father weren’t eager to talk about Mike even when they were alive.

I knew my mother saved the newspaper stories documenting Mike’s death. I had read them when they hit the front page of The Denver Post in 1976, and for many years I felt I had no need to revisit them. When I finally got around to asking my mother about the file’s whereabouts, Isabelle told me she destroyed those stories because she found them too painful to keep. I was startled, but I knew I could reconstruct Mike’s last days in the news archives when I reached that point in my life when I would need to revisit his death.

After Isabelle died in 2002, I said offhandedly to my father that I wished Mom had saved those clippings. Don told me that when he saw Isabelle toss the envelope, he pulled it from the trash and hid it away. The file existed after all—a sheaf of yellowing sheets and decades-old correspondence to document Mike’s difficult life in and out of our family.

I shouldn’t have been surprised that Don had the file, given my father’s fondness for list-making and timeline-constructing. He documented his family life as he documented his scientific research and fieldwork.

In my own time, I surely would want to reread those letters and stories. But not then. My own children were still middle-schoolers, Mike’s story was too complicated, my needs lay elsewhere. I was relieved to know the opportunity still existed, preserved in a file drawer in my father’s bedroom.

A few years ago, on a visit to my father in his Denver apartment, Don told me he had set aside the file. He felt it was time to pass it on, that I should take it. But when I left for home, I forgot the envelope. “Forgot.”

Don was then in his nineties, with macular degeneration taking nearly all of his sight. When I asked about the envelope on my next visit, he said, with anguish, that he had thrown it away by mistake as he was culling old papers. He had thought to toss something unimportant, but he misread the label and tossed the “Mike” file.

Disappointed, but philosophical, I reverted to my assumptions about the necessity of archival research. I knew I could rebuild the public chapter of Mike’s story, at least. And then, at the beginning of 2011, we moved my father from Denver to Salt Lake City, to live near us as he approached 95. We cleaned out his filing cabinet, and there it was, the envelope marked with my mother’s block letters, “MIKE.” The file had nine lives, and my father hadn’t jettisoned it after all.

Don lived only a few more weeks. I left his papers in boxes for months. When I unpacked them, there was the clasped manila envelope again, all that remains of Mike’s stories, along with a scatter of photos in our family albums.

The envelope feels incendiary. It’s taken me a year to open it. But, now, I do so. Finally, I’m ready to grapple with Mike’s life and death and to follow the story of my mother and her lost son wherever the details lead, further and further into the dark recesses of my family—and behind the doors I’ve barricaded in myself.

Stephen Trimble

Salt Lake City, February 2012

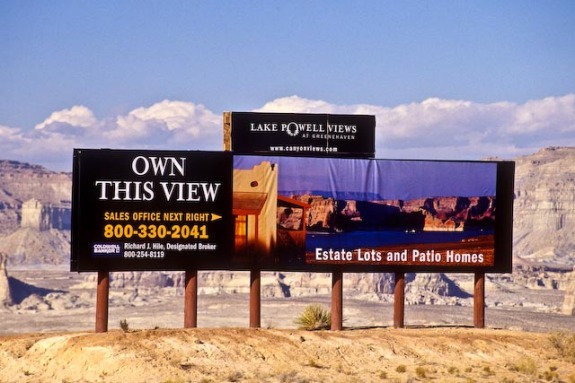

Own This View!

real estate sign, Greenehaven, Arizona

Last week, Arizona Governor Jan Brewer vetoed SB1332, which arrived at her desk with the imprimatur of the Arizona state legislature—and with language that demanded that the federal government turn over to the state 47,000 square miles of the state’s public lands. I may never have agreed with Governor Brewer before on any issue, but she got this one right. She acknowledged the clear unconstitutionality of the bill; she foresaw a nightmare for holders of leases on federal land while the bill made its way through the courts. And she acted with good common sense when she sent the legislation to the dustbin, using the same arguments any good conservationist would use.

Utah did not fare so well. Governor Gary Herbert signed our own version of a similar bill.

Last month, in an interview on our Salt Lake City NPR station, KCPW, I spoke in defense of managing public lands for the many and not the few. I shared the hour with Utah Representative Roger Barrus, one of the bill’s principal sponsors—though he refused to appear on-air with me; he would only speak alone and unchallenged. Today, I’ll be speaking to this issue again on Utah Public Radio’s “Access Utah” program.

I never cover all of my points in a half-hour interview or a 600-word op-ed. Since the issue won’t go away, I’ll post my notes here on THE BRIGHT EDGE. I don’t want to lose the research and the reasoning. Hence, this archive (or shall I call it a rant?), with considerable borrowing from BARGAINING FOR EDEN :

Each time I loop through twentieth-century environmental history I reach the same two contradictory conclusions: that we have made astonishing progress toward achieving Aldo Leopold’s land ethic and Rachel Carson’s sense of wonder. And that we still rarely rise above the old destructive notions of unbridled development, of land as commodity.

Is land a commodity, just another possession to generate income? Or is land inseparable from our roles as thoughtful and ethical beings forever woven into the web of living things and the physical world that sustains us?

Your answers to these questions predict your attitude toward Utah legislators’ request to take over 30 million acres of public lands. Your answers also underlie our anguished wrangle over the soul of the West.

I’ll admit that I have always believed in public lands as our permanent common ground. I use the word “community” more than I use the word “property,” the word “conservation” more than “commerce,” the word “planning” more than “profit.”

The reason we have 30 million acres of public land in Utah is not because the Federal government did not strive mightily to give it away—both to legitimate settlers and to speculators. They all tried, but Utah will never fill in. We are the second driest state in the continent. Because of our aridity, we are ecologically fragile. Because of climate change, our state will become both drier and more fragile.

In the arid West, much of the land turns out to be more profitable for the spirit than the pocketbook.

There is a direct correlation between aridity and acreage of remaining public lands. Nearly 65 percent of Utah is federal land, the second highest total in the nation—and Utah is the second driest state. Next door in Nevada—the driest state in America—83 percent of the state is owned by all of us.

The reason rural counties in our state have dismal economies isn’t because of neglect. They simply can’t support more people than they do. They are remote—for a reason. There aren’t enough resources for large populations nor is there enough water. We believe in growth for growth’s sake, in the inherent goodness of unlimited economic development—and we were the last state in the Union to form a Department of Natural Resources. We have the smallest acreage total of conserved private lands in the Rockies.

One third of our legislature has ties to the real estate and development industry; in past legislatures, the majority of members have come from the development industry. In many years, their biggest campaign contributions come from the Utah Association of Realtors. Our governor is the former president of that association. Between 75 percent and 95 percent of all subdivision parcels created in the Rockies are platted and sold without evaluation of the environmental, social, and economic impacts of that development.

So we are talking about a fundamental difference in values.

What these rural places (which are pretty much synonymous with public lands) have is extraordinary landscapes. There are no other places on the planet like the Canyonlands and Navajo Country of the Colorado Plateau. No experiences of solitude compete with the sweep of the Great Basin valleys in the West Desert. We all know and love the High Uintas and the Wasatch backcountry.

We also are in the top ten of urbanized states in the Union. New York has a more agriculture-based economy than Utah. We don’t see water as a limiting factor for population growth and economic expansion—but we should.

Ranching on public lands in the West no longer represents a dominant sector of the economy or the workforce. In the next ten years farming and ranching jobs will decline in numbers nationally more than any other occupation. Just 180 permittees run livestock on the 2.2 million acres of BLM land in the Richfield District an area with a population of 50,000. Services and retirement income, not resource extraction, are the growth factors here. Welcoming new people and new skills will grow the economy. Agriculture, on the other hand, has declined to just 15 percent of the jobs in Wayne County, and manufacturing (including forest products) to less than 4 percent.

Remote corners of the West that appear to be rural grow ever more tied to cities, just as the World Wide Web and the global economy link the far corners of the planet ever more completely.

The Governor and the legislators who support this bill speak of public lands as a “problem.” Ask the people of Utah who treasure their shared heritage of natural landscapes open to all if they think public lands are a problem.

Ask the millions of international tourists who come to southern Utah every year if they think undeveloped land and dark night skies are problems.

Ask the outdoor recreation industry that comes to Utah twice a year for its national convention because of our public lands if they think that national forests and wild country is a problem. That outdoor recreation industry contributes $5.8 billion annually to Utah’s economy, supports 65,000 Utah jobs, generates nearly $300 million in annual state tax revenues and produces nearly $4 billion annually in retail sales and services in Utah. The show attracts more than 2,000 companies and over 40,000 people from all over the world and amounts to $40 million in direct spending within the city. Do you think they will keep coming if we privatize our public lands?

Governor Herbert sounds like generations of Westerners before him when he complains that the director of the BLM, Bob Abbey, has more power over the lands in the state of Utah than he does. He asks to rebalance the state’s relationship with the Federal government—and he reprises the battle over Federalism versus states rights that goes right back to the founding of the Republic.

We fought a Civil War over this issue. Remember: the Federalists won.

The advocates for Utah ask for equality with the Eastern states in terms of private lands. Representative Roger Barrus uses the language of sovereignty. But we are too dry a place to be independent. We are embedded in the Colorado River Basin, and every management decision in the Utah deserts affects states from Colorado to California. We need to collaborate and plan. We’ll need help from the Federal government—our government—to survive droughts.

I often interview ecologists and climate scientists—and I’ve learned two bedrock truths about Utah and western ecology from listening to them.

First, Utah and the Colorado Plateau lie at the crosshairs of climate change, and we will need to strategize for resiliency as our environments shift with drought and rising temperatures. And, second, if we want to continue to revel in the natural communities we love, to live with large mammals as our companions on earth, we must maintain the connectivity of their habitats. Isolated refuges and preserves aren’t enough. This bill will lead only to further fragmentation.

Do you think the legislators are thinking about these threats? I don’t think so. But I know biologists in federal land management agencies who are among the leading international thinkers on these issues—and they work right here in Utah, under salary from the dreaded Federal government.

At the signing ceremony, Roger Barrus ridiculed the ability of the Federal agencies to manage public lands wisely. He says Utah has a good track record for managing public lands. But our state can’t even manage its state parks wisely enough to keep them open!

Our state will take over tasks that cost hundreds of millions of dollars. The combined Utah budgets of the BLM and Forest Service alone total more than $200 million. That’s every year. We will have millions of acres to manage—even if we sell off what we can, and we’ll have to continue to fight brush fires and cheatgrass invasion in the West Desert, manage grazing leases, enforce the law on millions of remote acres.

Utah citizens will continue to pay Federal income tax to manage public lands in other states. In Utah, we will be on our own.

Representative Barrus worries over the right issues: invasive species, changing fire regimes—and a nation crippled by debt without the money to fund management. But the only way Utah would have the funds to replace that Federal budget would be to vastly increase development—with constant court battles at every step, for we aren’t likely to do away with all the great Federal conservation legislation of our lifetimes.

He uses the State Institutional Trust Lands as a model—but the sole mission of SITLA, the state agency that manages our school trust lands, is to extract maximum profit from their lands. Conservation, wildlife corridors, strategies to mitigate climate change, management for ecological resiliency—none of this matters as much as profit. SITLA, by definition, is not a multiple-use agency.

Where did those school trust lands come from? Starting with Ohio in 1803, Congress began granting incoming states at least one square-mile section per 36-section township to support public schools. Utah received four sections per township as compensation for the vast amount of land retained by the people of the United States. Lawmakers considered most of arid Utah to be worthless and figured the state needed all the help it could get. Thirty percent of Utah’s private land started out as “school sections,” mostly sold in the first thirty-five years after statehood in 1896.

In a recent editorial, Lieutenant Governor Greg Bell rightly points out that national parks have at least an $11 billion maintenance backlog. The Forest Service has its own $3-5 billion backlog. Millions of acres of national forests risk catastrophic wildfire, and the majority of our federal grazing lands are in less than fair condition. The federal government won’t be able to find funding to dig itself out of its backlog hole.

He asserts that Utah will do a better job managing these lands. Where will all these billions come from? The only possibility: intense resource extraction and privatization. And I’m concerned about his ability to create a vast cadre of knowledgeable managers when he says: “Would we really build a McDonalds in Arches or destroy Natural Rock Bridge?” I think he means Natural Bridges or Rainbow Bridge National Monument, but I’m not sure.

The bill that Governor Herbert has signed proposes a Public Lands Commission to manage Utah’s newly acquired 30 million acres. We know how this commission would be appointed—from the power elite of our state, who believe in development to their core. Do they already have a transparent management plan laid out? If not, I find it worrisome and irresponsible that they would just “wing it” to create a process. I don’t think they’ll be transparent. I worry that they may not know where this mysterious “Natural Rock Bridge” is.

Where did those public lands come from? Did they ever belong to the states? Let’s take a quick spin through history.

Americans claimed 214 million acres claimed under the Homestead Act between 1862 and 1923. Of the 32 million acres of original entries under the Desert Land Act (which upped the homestead to 640 acres in 1872), only 8 million acres were finally patented to settlers.

Speculation and aridity led to millions of acres reverting to Federal ownership, to be sold or become part of the BLM lands.

In the 1870s, John Wesley Powell argued for 2560 acres per settler in the Desert West—and managing the arid lands watershed by watershed. No one listened. Instead, by 1889, over 1 million sheep and 350,000 cattle roamed the Salt Lake Valley and Wasatch Range. Ten years later, sheep numbers grew to over 3 million head. When a range specialist took a look at the unmanaged range in 1902, he saw complete deforestation, brushlands grazed to dust, ravines used as log shoots, eroded roads, mine tailing piles, slash and sawdust heaps, indiscriminate and recurring human-caused fires—environmental collapse.

By 1906, we had our first national forests in Utah—and the LDS Church supported their creation. Even so, sheep overgrazing and habitat destruction continued.

We did our best to sell and give away and allow to be stolen all those millions of acres of Federal land. We violated treaty after treaty with Indian people and appropriated their vast lands (that we had guaranteed to them in perpetuity) for settlement and development. This is what historians and scholars call the Era of Disposal. But it ended!

The 1934 Taylor Grazing Act brought down the curtain on disposal. In 1946, after a land grab by Western senators that reached too far, the Bureau of Land Management was created to manage public lands.

Ronald Reagan and James Watt tried again in the 1980s, but by then the country had come around to a new conservation ethic, including passage of the Clean Air Act, the National Environmental Policy Act, and the Endangered Species Act—all under the Republican administration of Richard Nixon.

The supporters of the 2012 bill call these laws a burden of bureaucracy and regulation. But as we insisted that business clean up pollution, we saved the lives of citizens. Because of the management under these laws, we have brought species brought back from the brink of extinction and preserved irreplaceable habitats.

The supporters worry about restrictions on access. What sort of access will citizens have if we privatize public lands? Given the passion for private property rights in the West, I think citizens will find their access considerably diminished if Congress acquiesces to these demands.

I can see alternatives: Why not block up the remaining school trust lands that checkerboard our state? Create a massive land exchange that removes state lands from parks, forests, and wilderness; concentrate them near towns, cities, and industrial areas where they can truly benefit schoolchildren. Conserve our wildland heritage intact and you grow the economy: In the last 40 years, the fastest growth in the West has been in communities adjacent to protected public lands.

Instead of doing everything we can to entice heavy oil and gas development that compromises our incredible heritage of wild land, and instead of spending the citizens’ money we would use as incentives—or in court battles—why not hire Jeremy Rifkin to help us convert to a distributed renewable energy economy? Rifkin is a big-picture thinker who advises the European Union on how to facilitate a Third Industrial Revolution—and Germany is leading the way.

Converging the Internet with renewable energies will allow millions of people to generate their own green electricity in their homes, offices, and factories and then share it across a vast energy internet, just like they now create their own information and share it online with millions of others. Utah would be much wiser to invest in this kind of visionary thinking that could sustain our economy in this new and challenging century, and we would support our schools in the process.

What the legislature is doing—what Representative Barrus is doing by refusing to have a conversation on the air with me—is to create the same kind of top-down insider decision-making that those same officials decried when President Clinton proclaimed Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument. To make progress, we need to talk with each other. We need to go find Greg Bell’s Natural Rock Bridge and break bread in its shadow and talk about its future.

The county-by-county lands bill process provides one possible route to this conversation. Everyone needs to be at the table to feel invested, to have their contributions to a final compromise. Only then do we have procedural justice.

Dan Kemmis, the former speaker of the Montana legislature and past mayor of Missoula, has imagined the creation of gigantic land trusts that would turn whole watersheds over to local compacts of states, Indian tribes, and citizens. He insists on two provisos: that the lands remain public in perpetuity, and that trustees manage them for ecological sustainability. That approach has real possibilities—but it embraces far more stakeholders than this current grab for power by Utah’s politicians.

Gale Dick, our treasure of a founder of Save Our Canyons here in SLC has suggested to me that “long-term bickering may be the solution, not the problem. After all, protection of the land, not harmony among stakeholders, is the goal.” We need to talk this out on the land we all love—not fire volleys at each other in court.

As Olympia Snowe said on the PBS Newshour on March 21, as she left the Senate in disgust:

“People view compromise as a capitulation of your principles. It’s not. What is the objective of serving in public office? I believe it’s problem-solving.

“I would recommend being open and listening to the people with whom you disagree—not just to the people with whom you agree. You can’t solve a problem if you aren’t talking to the people who disagree with you.”

Hyde’s Wall

My friend, Pastor Jeff Louden, asked me to post an entry on his Landscapes of Faith blog. (We are both on the board of Utah Interfaith Power & Light.) And so I become an emissary from the canyons of southern Utah to the world of the Lutherans! (perhaps I’ll run into Garrison Keillor…) I chose an excerpt from my essay in West of 98: Living and Writing the New American West, the fine anthology edited by Lynn Stegner and Russell Rowland and published by the University of Texas last year. I’ll reprint the entry here, as well.

In the long-ago spring of 1976, the side canyons of Utah’s Escalante River were more remote than they are now, and they are still pretty remote. My two buddies and I had driven without incident in our hand-me-down family sedans across the Circle Cliffs to the Moody Creek trailhead. We found no other vehicles parked at the end of the road. Once we set off on foot, we weren’t expecting to see anyone else for the next week.

We made camp at the junction of East Moody Canyon and the Escalante. In the lengthening iridescent light of late afternoon we wandered up East Moody Canyon. Each rounding curve brought new walls. Desert varnish streaked the crossbedded sandstone, black swaths across lavender and vermillion. Here, the color fields of Rothko; there, the bold strokes of Franz Kline.

One wall in particular drew me. I moved my tripod this way and that, aiming my camera past piñons and junipers to a canyon wall reflecting purples and mauves, textured with fractures and cracks. The light had bounced down between canyon walls from the sky and the stars, distilled to an unbelievable saturation. I had never seen such surreal and intense colors. Later, I realized Philip Hyde had photographed the very same wall for Slickrock and for his Glen Canyon portfolio. Over the years as I published my pictures of that place, I captioned them “Hyde’s Wall.”

We tore ourselves away from each mosaic of rock, tree, grass, and lichen in the endlessly changing gallery and strolled on, tantalized always by the next bend. We came to an amphitheater, the canyon’s curves arranged to form an echo chamber with three reflective surfaces.

A trickle of water in the streambed was enough for the frogs and toads. On that springtime evening they were calling enthusiastically, the cricketlike trill of red-spotted toads and the plaintive bleat of Woodhouse toads advertising their readiness for sex. Spadefoot toads added a third melodic line, a sawing snore, while the final accent came from the ratchety bark of the canyon treefrog—my favorite. They took turns, calling across the alcove, each song echoing individually and distinctly. Stage right, stage left. Then a pause, and a call from back in the cheap seats. We kept our distance to avoid silencing them. They created a fully three-dimensional audio space, and to lie back against a boulder and listen to them felt both intimate and voyeuristic.

Today, fewer and fewer canyon treefrogs call from potholes and desert streams. The Colorado River Basin lies squarely within the crosshairs of global climate change. Rising average temperatures are certain to bring warmer summers, more rain than snow, decreased spring runoff, and more frequent wildfires. Climate change will push every living community uphill until alpine tundra and alpine animals like pikas can retreat no higher and will be pinched right off the mountaintops of the southern Rockies. What will we do for water in this increasingly dry century?

Our edges are rounder, our destination closer. Gravity and time turn out to be equally inexorable. This same arc through time deepens our relationships with the places we love. The redrock wilderness has granted us refuge, repeatedly. The universe has provided us with a lifetime of chances to speak up for these remaining fragments of wild ecosystems.

Let’s take full advantage of these last few winding and glorious bends, missing no opportunity for joyful adventure and rising to each occasion calling for advocacy as we tumble toward the sea.

[Excerpted from “Tumbling Toward the Sea” by Stephen Trimble, in West of 98: Living and Writing the New American West. Lynn Stegner and Russell Rowland, editors. University of Texas Press.]

Telluride to Tuba City

As I used to read each new batch of essays that Ed Abbey published during the last decade of his life, I remember feeling grumpy. Why did he keep repeating himself? He always included a nod to his favorite bird, the turkey vulture. The same adjectives turned up over and over again to describe the same familiar rock formations. Was he just lazy?

As I keep recycling bits and pieces of my own writing for new purposes, I’ve grown much more tolerant over time. I’ve written about the Colorado Plateau for more than thirty years, so I am often asked to speak about the Canyon Country. To make my points most powerfully, I go back to tried-and-true images and ideas. I’m sure Abbey was doing the same thing.

I now believe that I’m mining my past work the way politicians create a political stump speech. We naturalist writers are framing our favorite landscapes and conservationist manifestos with the most powerful words we can muster. Once we’ve settled on that framing language, we are simply being good communicators when we repeat those carefully chosen frames.

We’ll never be as relentlessly successful in repeating our talking points as the conservative Republicans in Congress, who are implacably and terrifyingly skilled at staying on point. But Abbey’s turkey vulture and my canyon wren deserve to turn up repeatedly. And I now believe that’s okay—and effective.

So when Janet Ross at the Four Corners School of Outdoor Education asked me to speak in Monticello at the groundbreaking ceremony for their new Canyon Country Discovery Center on August 12, I was honored. I pulled out my favorite storyteller images and my well-honed Colorado Plateau talking points to create a new version of my stump speech for the occasion. And that’s okay.

Telluride to Tuba City: Making a Home on the Colorado Plateau

I wanted to learn a little more than I knew about my fellow speakers, so I poked around on the Internet a bit. I learned that…

Doug Allen, Monticello’s Mayor was raised in Salt Lake, but, he says, “San Juan County is home.” In the Canyon Country Discovery Center video on the Four Corners School website, he says, “We all love this land.”

I learned that…

Bruce Adams, the San Juan County Commission Chair used to be a science teacher. Now he applies himself to the science of raising hay. One of his students wrote, “You were my 5th grade teacher in Snowflake, Arizona in 1972. You were a difference-maker in my life! You treated me like the person I wanted to become. Though its unlikely you remember me, I will always remember and appreciate you. Thanks for being a positive influence on my life.” Scott Flake, Snowflake AZ

Bruce is still a teacher at heart. In that same introductory video he concludes his pitch to support the Discovery Center by saying passionately, “The story of the treasure that is San Juan County needs to be told.”

In October 2008 Bill Boyle generously spent some time talking with my class from the University of Utah, when we came to town to try to understand how San Juan County folks feel about their home territory. One of our students was particularly moved by his love for this land. She heard that affection and loyalty in Bill’s description of his home here—and she heard that love from others as well, from federal agency land managers like Kate Cannon, superintendent of Canyonlands National Park, to river runners, to ranchers like Heidi Redd out at Dugout Ranch. Bill convinced that student, Cynthia Pettigrew, that “Community conversations are essential; they serve as a reminder that every interest has a rightful stake in public lands and they give people the opportunity to build relationships based on interactions rather than speculation about opposing interests. We all have to learn how to give a little.” Wise words.

State Senator David Hinkins stated his guiding philosophy to a news reporter not long ago “sometimes an adversity can also be a time of opportunity.”

That astute observation says a lot about the possibilities presented to us by the Canyon Country Discovery Center. We still face the adversity of raising the funds to complete this dream. But it’s an incredible opportunity to expand the programs of the Four Corners School.

The Four Corners School states its Mission in this way:

to create lifelong learning experiences about the Colorado Plateau bioregion for people of all ages and backgrounds through education, service, adventure, and conservation programs.

And its Vision:

to build a diverse community committed to conserving the natural and cultural treasures of the Colorado Plateau.

We need some Definitions:

Conservation is a tricky word. Here is what Merriam Webster has to say about defining conservation:

a careful preservation and protection of something,

especially: planned management of a natural resource

to prevent exploitation, destruction, or neglect.

Lastly, we need a definition for the Colorado Plateau…

It’s not an isolated landform in the state of Colorado. It’s the vast network of canyons carved by the Colorado River, named by John Wesley Powell when he was the first to row those canyons back in 1869.

The Plateau is shaped like a heart. Picture that heart turned on its side—its two lobes wrapped around the Rockies, with the cleft somewhere around Telluride. Rivers form those lobes—the drainages of the Green and Colorado in the upper lobe. In the lower lobe, the San Juan River watershed reaches almost to Albuquerque, New Mexico, and the Little Colorado reaches deep into Arizona.

The Colorado River cuts across this heart, the deepest artery, the deepest vein, headed for the point of the heart, where the Colorado emerges from the Grand Canyon to flow out into the Southwest Deserts.

Monticello lies at the heart of the Colorado Plateau, on the rise between the Colorado and San Juan. What a fine place for an introduction to this Canyon Country.

From the mouth of the Colorado River at the sea, the Southwest rises northward in steps—concentric semi-circles from desert basin, to desert mountain, to the Colorado Plateau, and finally, to the Rockies themselves. Keystone to this circular Southwest, ringed by dry mountains, standing like a huge island above the deserts, the Colorado Plateau seems timeless. Its dramatic landscapes are icons. Its rocks are old, its canyons still new, its geology laid bare to even the least observant eye. Aridity and isolation have preserved Native ways here as much as anywhere in the West.

The archaeologists tell us that San Juan County was more densely populated in prehistoric times than it is today. And then the People (as the members of nearly every tribe call themselves) moved on, leaving much of the plateau to the light and the silence, choosing new homes, evolving into modern Pueblo people.

The Ancestral Pueblo people who once lived on Cedar Mesa—and at Mesa Verde and Hovenweep and Chaco Canyon—now live in modern Pueblo villages that span a 350-mile crescent from the Hopi mesas of northeast Arizona to the Rio Grande pueblos near Albuquerque and Santa Fe. Over centuries, these Pueblo people have become environmental wizards, the best dry farmers in the world.

Change keeps coming. Anthropologists say that the Navajo people arrived about 1400, reaching the Southwest with their Apache relations long after other tribes. The Navajo have incorporated the land into their creation stories, into their souls. They believe they have been here from the beginning—sheepherding, farming, and adapting. You can see this land in their elders’s faces.

Today, the Diné, the Navajo people, flourish in today’s Navajo Nation, the most populous Indian reservation in the United States. They are neighbors here in San Juan County, where they face both their traditional hogans and modern cinderblock homes east toward the rising sun below chiseled sandstone buttes and spires.

Ute and Paiute people continue to live on the plateau, as well—and one of those tribes retains their ancestral homeland just a few canyons away from where we stand, the White Mesa Ute people. Remember that the state of Utah is named for those Ute people.

Great spaces and high elevations make for stark clarity of vision, both literally and spiritually. The rock, time, space, and color of the Colorado Plateau forge a bond between people and land.

That bond extends to all the rest of us who have come here to make a home—whether we came with the San Juan Mission on the Hole In the Rock expedition in 1880, as pinto-bean-farming homesteaders in 1910, as uranium miners in the 1950s, or as National Park Service rangers in 2010.

The land turns us inward. The Colorado Plateau is a prayer turned to stone. We walk down secret slots into the Earth as we walk down the aisles of houses of worship, as we pass into sacred space in any tradition. We reach out to touch cross-bedded and sculpted walls, created by water as we are created by water. Music comes to us, the chords of rapids downcanyon, the singing of canyon wrens—the lilting paired notes of a musical waterfall. Light comes in rich and intense colors, the hues of royalty and holiness and fundamental emotion—monkish saffron and stately gold and the reds of damask and blood.

Each canyon shelters secrets. But to share them you often start in desert flats. An arroyo leads on, the dry streambed winding through clay hills baked to crumbles by sunlight. Aridity rules.

In parallel with the arcs of our lives, erosion reduces the cliffs of the redrock canyons of the Colorado Plateau to rubble. Frost pries away slabs of stone in the winter. Rocks crash downhill and roll to a stop. They sit, waiting, and then a flash flood moves them downstream, rounding their edges. Each boulder rides the chaotic churn of floodwaters, comes to rest for a time, and again pulses downcanyon, headed for the sea.

And so we live—tumbling, careening and ricocheting off events and people, then slowing to a stop, stagnant and still. Our journey shifts, and we lift once more into action. We rush into a new chapter of life and suddenly hit unforeseen barriers. We change direction. Eventually, we all come to rest in the great ocean.

Maybe this metaphor appeals to me because I love these slickrock canyons more than any place on earth. I’m equally sustained by the peaceful times—leaning against a sun-warmed alcove, basking like a lizard—and the lively times, when something extraordinary happens, when stormlight creates a moment unlike any other, when a new person comes walking around the bend and life changes, subtly or forever.

I turned sixty last year, and, inevitably, I’ve been reflecting on all of this change. I don’t feel old, but I realize that my childhood in the 1950s was nearly as close to the 19th century as it was to the 21st.

In that childhood, on family vacations to the Colorado Plateau, I tallied the national parks and monuments I visited. I made lists of parks I yearned to visit. My photo album from my teens consists of row after row of snapshots from the viewpoints at national parks, all carefully labeled.

What can I say? Once a nerd, always a nerd.

In 1964, when I read in National Geographic about a new national park in Utah called Canyonlands, I was fascinated. The writer told of discovering never-before-photographed arches hidden away in the sandstone maze of The Needles. I reveled in the fact that—just a few hours from our home in Denver—someone could still be an explorer, like Lewis and Clark or John Wesley Powell.

My geologist father made sure we visited that new park the very next year. He new this country. My father, Don Trimble, had mapped the Oljeto quadrangle here in San Juan County for the United States Geological Survey in 1952. He even discovered a uranium deposit in the course of that fieldwork. He was as eager as I was to come see a little of this new national park.

And so we dared the crossing to the Island in the Sky across the one-lane width of The Neck and bounced out to Grand View Point to unfold ourselves from our 1962 Dodge Dart stunned by the view. I still stop to photograph at those viewpoints—and I still define myself as a southwesterner, right down to my yearly visit to the dermatologist to burn off the skin damage from a lifetime of walking through the dazzle of the western sun.

And as a writer, I keep trying to organize my understanding of this changing West. Everything—all that change—rests on the Bedrock West, the land itself, an extravagance of mountains and deserts and two hundred Native cultures still intertwined with the holy Earth.

In our part of the West, these redrock canyons insist that you acknowledge geologic time. Plains and deserts, and the sky above them, create spaces so expansive that they can fill you with exhilaration and dread. Mountains rise precipitously to bar you from neighboring valleys that a raven could reach in a ten-minute flight on a good updraft.

We westerners must measure ourselves against this land. Drought, cliffs, distances. Alkali, arsenic, cheatgrass. Citizens of the Colorado Plateau spend a lot of time arguing about the highest and best use of this Bedrock West, of these millions of acres of public lands—drylands that remain public because they were too challenging and difficult for very many people to actually live in and try to homestead, to make a living.

We do well to take the long view. The Colorado Plateau, the Desert West, is a shape-shifter, as Native storytellers understand. Living in a landscape where the bones show, where the Earth itself reminds us daily of its history, we must look to each other for guidance, for a clear path into the future, trading stories, trading knowledge.

I imagine a Next West, a People’s West, where with a new awareness of the true nature of our home, we finally acknowledge that we will always live enmeshed in Place—and that to find our way we must collaborate in creating communities, from Telluride to Tuba City, rooted in healthy relationship, with each other, with the land.

That is more or less the mission of this building.

The Colorado Plateau is so big, so diverse, so dry, so fragile, and—still—so wild, that we need to understand what this Discovery Center can teach us to distinguish between the old dualities and ironies: lie from truth, boom from self-reliance, dream from desert, reality from romance.

We have the chance to move beyond the paralysis of old antagonists. Doug Allen is right: We all love this land. Newcomers value the same open space honored by generations of families tied to the land. If we all can keep talking, if we can cooperate, New Westerners can absorb the best of the Old. The Old can evolve with the New.

If old-timers can resist embitterment while they give up so much, they can teach the newcomers something about roots. There’s a positive spin on the change coming to us all. We have a brand-new chance here.

We can create a mix of rural and urban cultures that recognizes the distinctive landscape, fusing all the cultures and communities of the Colorado Plateau into a single image of the future—a Next West, the People’s West, where sixty million people will live in the once lightly settled interior West. Here, we can find a new geography of conservation in a post-mythic and wise West at peace with the great land, as it changes and copes and evolves.

When our great writer of the western landscape, Wallace Stegner, asked for the West to create “a society to match its scenery,” he didn’t imagine that shifting global patterns in climate would mean that both society and scenery would turn out to be in flux. In the canyons of this dynamic home place, in the tricky cultural currents we must navigate, my aging generation is running out of time to make a difference. Sixty isn’t old, but we clearly can’t dawdle. You younger people have the chance to do better.

Our edges are rounder, our destination closer. Gravity and time turn out to be equally unavoidable. This arc through time deepens our relationships with the places we love. The Canyon Country Discovery Center—first dreamed up by Bill Boyle and Doug Allen and brought to brick-and-mortar reality here on this lovely site by Four Corners School director Janet Ross, with a lot of help from a lot of people—will continue to grow those relationships for many generations to come.

Along the way, the Four Corners School will accomplish its mission. The people who will make their lifelong homes here and the visitors who are newly discovering the canyon country both will learn from this center’s educators the value of service, the joy of adventure, the sweet sense of refuge that comes with belonging to a community, and the gratifying responsibility to conserve the natural and cultural heritage of the Colorado Plateau.

Generation to Generation

Before I post the essay below (a talk I delivered as the keynote for the Rocky Mountain Regional Conference of the Association for Experiential Education at Utah Valley University on February 25th), I need to tell you what led me to write it—which will explain my long silence on The Bright Edge.

My father, Don Trimble, has lived in Denver since before I was born, moving with my mother from my childhood home to a retirement complex in 1999 and continuing to live there after her death in 2002. He spent his days listening to recorded books and sharing dinners with a small band of friends each evening. At 94, he couldn’t see much, hear much, or walk very far, but he still said, “All things considered, I’m doing well.” And he remained amazingly sharp.

Don began to decline in November, after a small stroke. We made the decision to move him to an assisted living apartment just a mile from our house in Salt Lake City. He agreed, feeling for the first time that his life in Denver wasn’t rich enough to keep him there.

On January 5th, my wife, Joanne, and I headed east across Wyoming in our red Toyota pick-up to pack up Dad’s belongings. Joanne and Don would fly back to Salt Lake. I would follow in the truck, pulling a U-Haul trailer filled with his furniture.

We spent the first night in Rock Springs. The next morning dawned cold and clear, and we headed east on I-80 on a spectacularly sunny day. There hadn’t been a trace of snowpack or ice for hundreds of miles. We sailed across Wyoming, commenting on how lucky we were to have perfect weather for a midwinter drive. I set our cruise control at 78 mph, my default speed when the posted limit is 75.

About thirty miles east of Rawlins, as we approached Elk Mountain, I noticed a glint of reflection off the road. We felt the back tires lose traction. The back of the truck was filled with empty boxes, packing peanuts, and bubblewrap. No weight over the back tires to help. We began to float.

We veered right. I corrected, but didn’t touch the brakes. We veered left. As we headed into the median—still at 78 miles per hour—I blacked out. The world simply clicked off. In a wink, everything ended. I now know that dying in a crash could be instantaneous and painless.

But I woke up, came to, returned to consciousness—with the truck resting on its side. I was curled up in a ball between the steering wheel and the snow a couple of inches away. The window was gone. The snow turned red as blood dripped from my head.

I wiggled the various parts of my body, and everything worked. I realized that I couldn’t be badly hurt. I called for Joanne. She answered, telling me that she was okay. And at the same moment that I woke up, people arrived at the truck. A woman held my hands. I couldn’t see her, but she told me that her name was Alexis; she was a nurse in Lander.

She asked me the date. I couldn’t tell her. She asked me the year. I wasn’t sure whether we were in 2010 or 2011. She asked me the president, and I said “Barack Obama!” with such gusto that Joanne knew then I would be okay.

Joanne remembers saying to herself as we rolled: “But what about our plan? What about Don’s going-away parties in Denver? What about the move?”

In that moment, everything changed. The ordinary became the extraordinary.

While I blacked out, Joanne remained fully conscious as the truck rolled three times before it came to a stop. She tells me that the accident was incredibly noisy, and she didn’t know what had happened until the people who saw us go off the road described seeing us go airborne as we tumbled.

Those Wyoming folks know what to do at an accident scene. Reaching through the smashed windows, they wrapped us in blankets and heavy coats. They pulled mittens and gloves onto our hands. They set up a windbreak with the plywood sheet that had been in the truck bed. So many people told us their own rollover stories over the next few days, we decided that the rollover is clearly the Official State Accident of Wyoming.

Within five minutes a patrolman arrived, cut Joanne’s seatbelt, and helped her out of the truck. He later told us that we hit a tiny patch of ice that he couldn’t see until he got out of his cruiser. He also said that once we lost traction, there was nothing we could have done. We were goners. He also told us we were incredibly lucky to have survived relatively unscathed. Moral: seat belts work.

Joanne had a bruised shoulder, an injured tendon. Shattered glass had showered my scalp, hence all that blood. But my network of scratches and clots was superficial; none required stitches. Once the EMTs and extraction crew had cut me out of the truck by peeling off the roof and once the ambulance had transported us back to the Rawlins hospital and once the ER doc ordered X-rays, we discovered that I had a collapsed lung.

The new plan evolves moment to moment, and we attempt to maintain a zen-like attitude of calm in its face. Two days in the Rawlins hospital (where 80 percent of their patients come from I-80 accidents). A chest tube to reinflate my lung and drain my chest cavity. Incredibly kind new friends in Wyoming who bring take-out Thai and Mexican dinners. Another kind couple who drive us to Fort Collins, Colorado. An old friend who meets us there and takes us to Denver. Other friends and family who help with donation runs as we sift and sort through Don’s stuff.

And we’re off. The plan has shifted. We’re two days late. But Joanne and my father fly to Salt Lake on January 11th. I follow the next day—the first day the doctors have said that flying is safe after my collapsed lung.

Don moves into his apartment, sparsely furnished for now. He arrives Tuesday night. He begins to settle in a bit on Wednesday and Thursday. We visit. And on Friday morning, we swing by to pick him up for his first appointment with his new geriatric doctor.

He’s not feeling well. He’s had severe diarrhea that morning. Once in the doctor’s office, he begins to vomit, as well. He had taken a round of antibiotics in December, and it quickly becomes clear that those strong drugs may have cured his throat infection but they also wiped out his healthy intestinal flora. He’s now been recolonized by nasty bacteria.

The doctor is concerned about dehydration, and he admits Dad to the hospital, wheeling him from his office at one end of Salt Lake Regional Medical Center to the ER at the other end of the building.

Dad continues to fight, as a cascade of illness descends upon him. The stress of the bacterial infection in his gut (Staph, Clostridium difficile) leads to a heart attack and a stroke. He comes down with influenza. The gout arrives, which makes even the smallest brush against his skin incredibly painful. His kidneys begin to go haywire.

After twelve days of hospital care, we know that Dad can never regain a quality of life that he would find acceptable. He might beat back a couple of these illnesses—only to be warehoused in a nursing home for a few months before something else gets him. And so he moved to a residential hospice, slipping away on his fourth day in that calm and soothing room.

Don had his wits until just a week before he died. He was still engaged with the lives of his grandchildren from his hospital bed, still hopeful that the doctors could cure him, as they had so many times. But when we told him that they couldn’t, he relaxed into a peaceful place. With shining eyes, he told Joanne, “I’ve had a wonderful life.”

MAPPING THE GEOGRAPHY OF CHILDHOOD,

GENERATION BY GENERATION

My father, Don Trimble, died on January 30th—almost exactly a month ago. Next week, he would have turned 95.

My dad lived an entirely successful life. He was a successful son, close to his parents and embedded in a wide circle of aunts and uncles and cousins in his childhood. He was a successful husband, married with glee to my mother for 54 years. He was a successful father, grandfather, and father-in-law. He was a loyal friend, a politically engaged citizen, and an accomplished scientist.

And yet I was struck by how many friends and family singled out one strand in my father’s life when they composed their sympathy notes. They noted his relationship with wild country, a connection he passed down to me, and a connection that my wife and I have strived to pass down to our two children.

You can’t be certain just how your kids will take to these experiences. Establishing a relationship with nature happens almost physiologically, growing from basic personality. Experience in the out of doors may allow such a bent of personality to blossom. To our great disappointment, we may not see that flowering. We may drag our sons and daughters on endless hikes and camping trips, and the inoculation may never take. We have no guarantees. We can only be enthusiastic experiential educators, teaching—as you all understand—by using the power of direct experience.

We can only play matchmakers between our children and the Earth.

If I am going to talk with you about my own experiental education, I must talk about my father. And that quickly leads me to my father’s death and to these cards from friends that make me think about how connections with nature have become a tradition in our family, an ethic carried from generation to generation.

One friend captured this emotional thread succinctly in her note:

Losing your father has brought back a flood of memories of my father. They are such large figures in our lives and, for both of us, that is where the deep connection with the earth began. All I can say is: what they gave us lives on and is passed on. It is the only eternity I know of, and it is a lot.

Where did this deep sympathy with the earth come from, this core value that my father so successfully taught? I’ve written about this in my most recent book, Bargaining for Eden, and in my essays in The Geography of Childhood. Many of the stories I’ll tell you today come from these books. In an effort to analyze the continuum of values in our communities, I’ve tried to understand the origins of my own values.

Not everyone sees the earth as holy, as a place of refuge, as a precious resource that demands restraint and grants relationship. What made my lineage of smalltown Westerners yield a family of conservationists rather than a family of capitalists looking at the earth as an inexhaustible menu of commodities to devour?

For my father, this journey started on a North Dakota wheat farm.

He was born in Westhope, North Dakota. West and hope—the destinies and desires of thousands of dreamers caught up by the frontier distilled in two words. The town, co-founded by my great-grandfather, had existed for just thirteen years when “Doc Charley” Durnin delivered tiny, premature Donald Eldon Trimble and kept him alive by incubating him in a shoebox placed in the office oven. March 6, 1916. Baby Don’s parents, my grandparents, were authentic pioneer offspring. I heard their stories as a child, and they brought the opening of the West close.

My grandmother Ruby Seiffert was one of the first white children—as the family stories always put it—born in that part of North Dakota in 1892. That family line makes me cringe, now, after listening to hundreds of Indian people during the last 25 years remind me that many, many Native babies were born in Dakota—Lakota country—for many centuries before my own ancestors turned up.

The Seifferts, Alsatian and Scotch immigrants, had made their way west through Canada, finally crossing south over the line to North Dakota in the 1880s. My grandfather, also christened Donald Trimble, came from forebears who followed the American frontier westward from Maryland to Ohio, then Iowa, then on to North Dakota.

This was the homestead era, and the Trimbles and the Seifferts claimed land for their own. Public land was simply unhomesteaded land, and that’s where the men went duck hunting in the marshes, where young Ruby Seiffert and Don Trimble courted by hooking the sidecar to my Grandpa’s Indian motorcycle and bumping over the Turtle Mountains to Lake Metigoshe for picnics.

In Wallace Stegner’s pithy words, the families who came west at this time were either “boomers” or “stickers.” The boomers followed their dreams, booming and busting but always refusing to knuckle under to the reality of the dry West, always refusing to stay put and “stick.” My great-grandfather Grant Trimble started as a boomer.

The bust came in 1912, when Grant lost all his money in the wheat futures market. While cleaning out his office he found the deed to an apple orchard in Washington that he’d won in one of his business deals and forgotten. It was all he had left. And so the Trimble clan moved to Toppenish, a small Indian-agency town in the Yakima Valley. My father and his parents followed in 1922, leaving behind my father’s pony—and a few chunks of flesh from his hand, lost to a threshing machine.

Unlike the tragic arcs of the boomers dramatized in Wallace Stegner’s books, Grant Trimble gave up his wilder dreams. He transformed the Trimbles into settlers—“stickers”—for the remainder of the twentieth century.

In my childhood my paternal grandparents lived at the far west of our family space. In my father’s hometown of Toppenish, my grandfather and his two brothers and three sisters all lived within a few blocks of each other. My grandmother’s family remained behind in Dakota, and she remained resentful about that wrenching move so far from her family for the rest of her long life.

The Trimbles stayed close, interdependent, with the special affinity that connects those with a shared past—in their case, the boom times back in Dakota. They were townspeople now instead of farmers who worked long days at physically demanding tasks; they became small business owners and gained weight. They took to calling themselves the “ton of Trimbles.” They would spread their Adirondack chairs in a backyard circle and sip iced tea, recalling their adventures on the Dakota farms and prairie, reliving the golden memories of their youth.

Those Toppenish backyards contained some of my first wild places. The great evergreen tree that sheltered my grandfather’s fishing boat, where I would hide in sharp-needled shade. A cement-lined fishpond. A dusty alley with hollyhocks and bumblebees. These are my fundamental memories, from a time almost beyond memory. I can tell just how primal because when I recall those explorations, diving deep into that ancient lizard brain where awareness begins with scent, I smell that dust and those pine needles as much as see them.

From Toppenish the Trimbles looked up to the western horizon every day to see if their mountains were visible—the sublime glacier-covered half-rounds of Mount Adams and Mount Rainier. These were hovering presences in their lives. Even more so for my father, who hiked and climbed with the Boy Scouts as a kid and reached the summits of these Cascade volcanoes before he graduated from high school. He told me a month before he died that those climbing trips were the most important experience of his youth.

My father was not only a strong hiker. He was a good sleeper on rough ground. He laughed with chagrin when he told the story of a trip that tested his ability to snooze through anything. One long-ago morning he was still sleeping soundly when his friends tugged him downhill and halfway into the creek that tumbled past the campsite. The sun was well up when Dad finally woke up to the hoots of his scout troop—his floating sleeping bag and soggy feet bobbing in cold mountain water.

As a teenager, he took road trips with his pals, saving his money for gas so that he could see the spiky saguaros on Picacho Peak in the Sonoran Desert, the Grand Canyon, the Great Southwest. When his family visited North Dakota, they detoured to Glacier National Park and to Yellowstone. He loved mountains, he loved the outdoors.

A scout leader who was an amateur geologist opened Dad’s eyes to the land as a place to learn from as well as to recreate. And so Don studied geology in college so that he could work outside—putting himself through school during the Great Depression with stints as a mucker in hardrock mines. That’s mucker with an “m”—the most elemental physical labor—the worker who goes underground to clear the broken rock and ore shattered by explosives.

After World War II deprived him of his home landscape during a three-year exile in the South Pacific theater, my father was delighted to be back on the road in the West. He had heard that the United States Geological Survey was hiring in Denver. At thirty, footloose and in need of a job, this sounded good to him. He moved, within two years married the office clerk-typist—my mother—and spent more than thirty years as a USGS field geologist.

Dad and his fellow geologists and their wives were my primary childhood circle. These scientists did field work in summer in wild country all over the West, then returned home to Denver in winter to work out the meaning of their notes and maps, eventually publishing their theories as monographs. Their work verged on exploration, beginning their careers less than fifty years after John Wesley Powell had supervised work in some of the same places.

The landscape where Powell and his fellow geologists first made their mark was the Colorado Plateau, that great maze of canyons carved by the Colorado River. My father introduced me to these places on family trips. Later I worked in the canyon country as a park ranger. Today my retreat—my Eden—rises on a sandstone mesa with views across public land to a national park in the heart of the plateau. My imagination travels far but always comes home to these canyons.

The anti-intellectual stereotype of masculinity in the West veers in another direction entirely—that of the Hollywood cowboy who turned up in the western movies and television series of the Fifties, a man of the land but one who is driven to possess, own, and dominate—quick to take up arms to defend his property. Americans fancy this ahistorical stereotype. We imagine these mythic heroes as our leaders—and we often elect to the presidency men who play to that myth.

My father and his friends, by contrast, were men who drank and swore but treasured clear thinking and well-spoken ideas. They socialized as couples, women and men together. With plenty of World War II footage on the black-and-white television screen of our living room, I knew what they had done in the war a few short years before. Now “going out with the boys,” for them, meant getting together with their sack lunches at the office to talk politics, argue theories, and banter. They saved their extra energy for climbing mountains and anonymous ridges, intent on deciphering the story of the landscape. Mostly irreligious, geologic time was their gospel.

Their fieldwork mixed the physical and the cerebral. They drove Jeeps and forded rivers and sweat-stained their hatbands. They mused in grand scale, comfortable with the millions and billions of geologic time, but they spent their days in physical contact with the earth, picking up rocks warmed by the sun, collecting rough horn coral fossils and knife-sharp chunks of obsidian, kneeling to measure grain size and the angles of rocks jutting from the surface of the planet. Mapping and photographing and drawing in their journals, these men made art while doing science.

And they accumulated stories. My father told of being cornered by ornery badgers, of encounters with lonely Basque sheepherders who wanted to talk but couldn’t speak a word of English, of vehicles breaking down sixty miles from town, of coming across a beached Columbia River sturgeon ten feet long.

He worked on the Navajo Reservation in Monument Valley during the early 1950s uranium boom and watched with interest as Navajo families circled through the rhythms of their lives and their sheep-centric economy. He and his field partner kept a permanent camp at the edge of the airstrip at Oljeto Trading Post for months. They played brutal practical jokes on Ed Smith, the trader. Ed hated snakes, and one story involved a dead rattlesnake that tumbled out of the mailbox and into Ed’s hands, to his horror.

Early on, my dad made authentic strides in his science, verifying the theories of J. Harlan Bretz about catastrophic flooding from glacial Lake Missoula creating the channeled scablands of eastern Washington. Channeled scablands: what an irresistible name for a landform.

In going through my father’s papers last week, I found a full-blown draft for a memorial to be published by the Geological Society of America after his death. Ever the precise archivist, he wanted to get straight the stratigraphy of his own life. Dad had written similar memorials for his friends, who dropped away one by one over the years, as he outlived so many of them. I think he must have thought, “I know how to do this, so I may as well write one for myself”—even if it was a little creepy, writing his own professional obituary.

Toward the end of this manuscript, he summed up his major accomplishments in one paragraph: Don Trimble mapped the geology of more than 3,500 square miles of the United States. He was the only US Geological Survey geologist to discover a uranium deposit (in Monument Valley, in 1952). He added greatly to our knowledge of the results of catastrophic flooding from Pleistocene lakes Missoula and Bonneville, and established a basic stratigraphy for late Precambrian rocks in southeastern Idaho.

This was his list, these are his words, his description of the work he judged memorable.

Part of the family lore came from his friends’ fieldwork, as well. Irv Witkind, for instance, famously woke up one night when his camp trailer at Hebgen Lake, Montana, started moving. He leapt out of bed, thinking the chocks must have shifted and the trailer was rolling downhill into the lake. To his delight (as a scientist), he found himself at the epicenter of the 1959 Yellowstone earthquake. He threw on his clothes and started dividing his time between helping survivors and measuring fault scarps. Two other cohorts of my dad predicted the Mt. St. Helens eruption.

During field seasons, visitors with special skills came to consult on Dad’s geological puzzles: a paleontologist to identify fusulinid fossils, a geochemist to gather samples to date using radioactive decay. This was dinner table conversation when I was ten, twelve, fourteen.

My childhood summers reeled out as adventures, their rhythms dictated by the fieldwork assignments of my father. When school ended each spring my parents and I drove west through Wyoming. In each outpost of home in Idaho or Oregon we rented a house in the town closest to my father’s mapping area.

Our summers had the open-ended allure of a vacation heightened by the dare of being on the road. By this time my father had already been driving the West for twenty years, and he plotted the family route from mountain to mountain and restaurant to restaurant. He loved the cool rise of the peaks as much as he loved the flake and fruit of homemade berry pies. As we drove he provided a running commentary on history, geology, and geography.

Isabelle, my mother, made sure we maintained our sense of humor and didn’t romanticize the emptiness too much. The three of us would croon “Why-O-Why, Wyoming” and dissolve in giggles. She teased my father and me when we enthused over landscapes she saw as barren “dirt,” when we rhapsodized about our love of the thunderous open spaces, no matter how nondescript.

My mother drove our Dodge, my father the government Jeep. When I rode with my mother, we looked for music on the AM radio, hoping for jazz. When I rode with my father, he told me stories. When we all rode together during vacations, we alternated between these diversions. Boxes of gear for the summer’s field season filled the rear of the Jeep and the trunk of the car: dishes, clothes, cameras, map cases, a Brunton compass, rock sample sacks sewn from white canvas and permanently scented with acrid basin and range alkali dust, my bicycle (and, once, in the rear window, my pet store turtle in a Skippy peanut-butter jar, forgotten and inadvertently boiled when we stopped for lunch one day).

Laramie was the first town out from Colorado: windy, railroad-dingy, a line of motor courts with cowboy neon fashioned into branding irons, bucking broncos, and buckaroos. On across Wyoming we drove, past broken-down gas stations that constituted most of the towns: Red Desert, Wamsutter, Point of Rocks, Medicine Bow. This run of the open-space West stretched as wide as the Cinerama screens in its cities, out to the limits of peripheral vision, where you knew it kept going. When something happened in that emptiness—a dust storm, a rainbow, a fleet of pronghorn dashing across the road so close I always remembered them actually leaping over the hood—it made my day.

On these long-ago evenings we would stop for the night at Little America, the motel and truck stop that punctuated the windy middle of nowhere in western Wyoming. Gleeful to be out of the car, we would shower off the sweat that came from driving before air conditioning became commonplace, with the windows open and my parents smoking.

While my mother and father relaxed at the bar with their before-dinner gin-and-tonics, and again, the next morning, when they lingered over coffee, I was free to wander around Little America, exploring.

I walked to the edge of the vast parking pads, where cement ended abruptly at the brink of what earnest ranchers in western movies called “Big Country.” From this frontier of the mid-twentieth century I stared into empty red-desert scrubland, the tantalizing space of Wyoming, and squinted up Black’s Fork toward Fort Bridger; shrinking under too much sky, I dreamt of the time when mountain men were the only Europeans for hundreds of miles.

In the beginning I needed this safe perch to confront the great North American space. I wasn’t yet ready to immerse myself in it. I looked in from the edge, from the road, from the car window, from motels at the periphery of crossroads towns—bunkhouses on the rim of wildness.

Never Summer Range, Snowy Range, Wind River Range, Horse Heaven Hills. Rabbit Ears Pass, Togwotee Pass, Lolo Pass, Chinook Pass. Longs Peak, Pikes Peak, Grand Teton, Mount Rainier. Some people remember from childhood the names of cherished baseball or football players. Others can recite still the multisyllabic names of molded plastic dinosaurs. My own remembered litany consists of place-names.

“Stevie, where do we turn?” my father would ask as I stared at the land charted in the folds of paper on my lap. My father, of course, knew which road to take at the next town. He also knew that I loved being trusted to help find our way.

During my childhood, the best highway maps of the western states came free from Chevron stations, in places like Rawlins, Wyoming, and Pendleton, Oregon. Stacked in wire racks coated with dust cemented in automotive grease, the maps waited for discovery, state by state. Down the road, I studied the air-brushed mountain ranges and passes and asked my father if I had them right: “Are those the Absarokas?” “The next bridge ought to be the Sweetwater River; tell me when we get there.” He pointed out Big Southern Butte and Twin Buttes, landmarks of the Snake River Plain, and I tried to find them on the map.

I searched the maps for the little red squares that marked “Points of Interest”; my questions about these cued my father’s steering-wheel lectures about western history and geology. “Maryhill Museum: what’s there, Daddy?” “What happened at Big Hole Battlefield?” “The map shows Crystal Ice Cave ten miles off the highway. Do we have time to go?” From my father, I learned about the differences between gneiss and schist, the route of Lewis and Clark down the Clearwater, and how Chief Tommy Thompson used to fish for salmon at Celilo Falls on the Columbia River before the dams.

Let’s make sure I don’t drift into mythmaking here. As a child, I wasn’t all that interested in geology. I often humored my father, half-listening, but couldn’t help but absorb at least some of his narratives. He cared deeply about this story; he was a born teacher, and he persuaded the USGS to publish non-technical bulletins he wrote for the general public about the Colorado Front Range and the Great Plains. He taught geology to families at Rocky Mountain National Park at the summer camp run by the National Wildlife Federation. My father’s passion for the rich landscape history that surrounds us continued to the end of his life.

That passionate connection to the natural world can begin with snakes, shells, or stars, birds, beetles, or blackberries. For me, connection started with the land itself, the bones and ligaments of the naked Earth exposed on the rocky surface of the arid West. Geography seeped into me, a bedrock awareness of landscape and place.

This attentiveness to landscape—I’ll call it geophilia in parallel to what E.O. Wilson calls biophilia—goes way back in our genes. We learn our homeland from stories, just as we learn nearly everything from stories. Anthropologist Keith Basso has noted in a wonderful book called Wisdom Sits in Places that Apache children in the Southwest constantly hear their elders link landscape features with the ethics of living correctly as an Apache. Listen to Benson Lewis, a Cibecue Apache elder:

I think of that mountain called “white rocks lie above in a compact cluster” as if it were my maternal grandmother. I recall stories of how it once was, at that mountain. The stories told to me were like arrows. Elsewhere, hearing that mountain’s name, I see it. Its name is like a picture. Stories go to work on you like arrows. Stories make you live right. Stories make you replace yourself.

Each summer evening, my father came home, picked the wood ticks from his clothes, and showered off the dust and reek of sagebrush. After dinner, hunched over the kitchen table, he painstakingly inked his penciled field notes about contacts, dips, and faults onto more permanent mylar maps. In winter, in his Denver office, he worked with the maps still more, writing about the geologic history he had untangled from the land he had walked over.

In my childhood, I chose my father’s lineage for my connections. Geology was the bedrock underlying patriarchy. Science was our religion, western history and natural history our tribal lore, the public domain of the West our Holy Land. Like my father, I took as my prophets the pioneers and mountain men, the explorer-scientists and writers journeying and journaling across the continent, and paid due respect to Lewis and Clark and to my grandfather’s pioneer energy.

A subliminal message ran through this history: that government was good. From Lewis and Clark themselves to Powell and the nineteenth-century surveys, to Aldo Leopold and Bob Marshall’s invention of the modern concept of wilderness while working for the Forest Service—the stories that nourished me featured federal bureaucrats as heroes. I grew up with the assumption that civil servants did visionary work.

The visionaries’ disciples were the men of my father’s generation, not long back from the war, returned alive to family, to good work, and to the canyons and deserts and rivers and mountains of the West. These were the places that gave them their stories. These were the places that make us who we are.

My wife, Joanne, and I did our best to expose our children to wild country. We took road trips. Just as my father did with me, I tried to pass along my love of the country as we drove across the West.

When my son was eight, he and I drove from Santa Fe to Salt Lake City on our own. Jake and I rolled off along the bike path below Telluride, Colorado, pausing for an interval of kid activity away from the truck. (Yesterday was “Skateboard Day;” today is “Rollerblade Day.”) Across the San Miguel River, the mountain wall reared above the valley’s thread of meadowlands. Clouds softened the greens, the even light mapping the mosaic of forest trees.

I asked Jake to come to the fence and to look across to the oversized mural of forest colors. I started pointing. There: light green aspen. And, see, over there: dark green fir. Below, along the stream, a colonnade of Colorado blue spruce.

He listened. And then, wholly without guile, he said, “Why are you telling me this?”

A second-grader whose passions were soccer and rock-and-roll, he wasn’t thinking about where he fits into his home.

His question was fundamental, though. There we stood, enfolded by the New West: Telluride Mountain Village, townhouses, gondolas, cappuccino, and all. And I asked Jake to see past the pleasures of the asphalt path to the wildness of the mountain and forest.

I’ve thought about how to truly answer Jake’s question: why know these things? Why know that the crinkly twigs from these spruce make the best kindling in the Southern Rockies? That Pleistocene glaciers carved the flat bottom of this valley? That hundreds of these aspen trees connect underground in clones sprouted from a single seed ten thousand years ago—and that climate change threatens the survival of these historic clones? That our hillside drains into the San Miguel River, which flows into the Dolores, which flows into the Colorado, which dies repeatedly in reservoirs, resurrected below each dam, gradually drained of its wildness, as it crosses the continent in its descent to the Sea of Cortez? That the whole watershed is teetering on the edge of drought, endangered, carrying as much change downriver as it does snowmelt?

Just as we learn the nuances of the bodies of our lovers, slowly, tenderly, we walk over the land and listen to its stories to find our way to the heart of the West. To establish a relationship with this land, to live ethically here, we must think about consequences.